| Home |

| Recreational Diving |

| Technical Diving |

| Aqua Dive Academy |

| Coron Philippines |

| About Us |

| Price List |

| Contact |

THE HISTORY OF THE CORON WRECKS by Peter A. Gallo Aincent History............................. Naval Intelligence.......................... Conduct of the War........................ The Merchant Shipping problem........ Tactics...................................... The Coron Raid............................. The Result................................... The Research Effort........................

Where does the story begin? Ancient History

The chain of events which led to there being a concentration of wrecks in Coron today, actually began long before Pearl Harbour and the beginning of the War in the Pacific. In 1898, as part of the Spanish American War, Admiral Dewey sailed into Manila Bay, took one look at the assembled might of the Spanish Fleet and said the immortal words “Fire when ready.” About 10 minutes later, the Spanish-American War in the Philippines was over, and the United States had a strategic interest in what happened in the Pacific from then on. After they proceeded to kick the crap out of Imperial Russia in 1905, it was patently obvious to a blind man that the only threat to US interests in the Pacific was Japan.

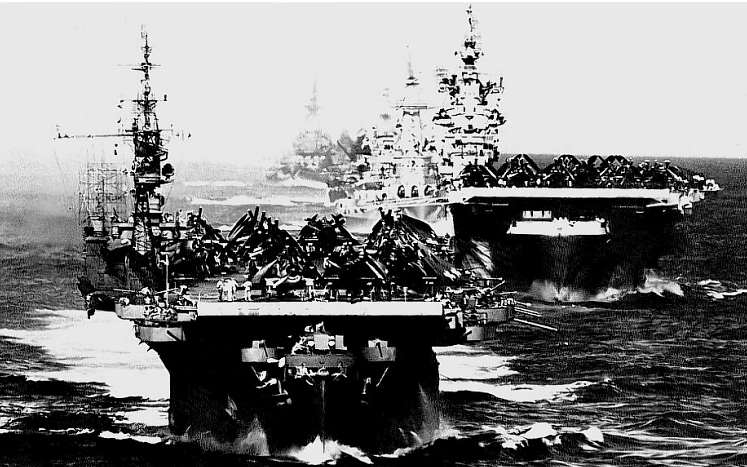

On December 7th 1941, the balloon went up, Japan had 8 aircraft carriers and 11 battleships, the US Navy had 6 carriers in their Pacific Fleet (with another one under construction) and their battleships either rested on the seabed of Pearl Harbor or were in need of repair from the damage inflicted on them.

At the beginning of the war in the Pacific, the Japanese Navy was bigger, stronger and better equipped, their planes were better, their torpedoes more effective. The United States only had two advantages;

Both of these advantages contributed to the story of Coron. Naval Intelligence

After Pearl Harbour, US Naval Intelligence had no significant human sources, no captured documents and little captured material, and no way to use photographs against a moving fleet. Only signals intelligence promised any hope of providing a picture of Japanese intentions and capabilities.

Navy intelligence efforts against the Japanese went by a variety of code names, one of which was "MAGIC." Technically, the code name Magic applied only to signals intelligence efforts directed against the Japanese diplomatic cipher produced by the machine referred to as "Purple."

Anyway, US naval code breaking effort had really began in 1921 when the Office of Naval Intelligence got a new director, Captain Andrew Long. Long significantly increased the number of intelligence personnel and language students at the American Embassy in Tokyo. Then, in 1924, Lieutenant Laurence Safford took over the Research Desk in ONI's Code and Signal Section. Safford deserves much credit for the founding of the Navy's system of communications intelligence. Among many efficient and foresighted steps he took, Safford organized a team of cryptanalysts to decode Japanese signals. The group members had one major problem: they had no Japanese signals on which to exercise their skills. To remedy this situation, the Navy established a radio surveillance unit on Guam in 1925, and they started listening….

By the late 1930s, Japan had fallen into the hands of its militarists and allied itself with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. America could not remain oblivious to the increasing threat. As one means of fighting that threat, the Navy, (having already cracked “Purple”, the Diplomatic Code) turned its attention to breaking the Japanese naval code.

The Japanese naval code in use just prior to Pearl Harbor, was referred to as JN-25 (Japanese Navy. Version 25), consisted of thousands of random letter groups that were enciphered prior to transmission.

A message would first be encoded by the Japanese: then, drawing on a stock of 100,000 five-digit members mixed at random (an 'enciphering table'), the clerk would convert into a ciphered text the already encoded message. Thus the Americans had to 'strip' the cipher before the coded signal could be bared and broken.

Nonetheless, American code breakers stationed at Pearl Harbor, led by Commander Joseph J. Rochefort, managed slowly, oh so slowly, to crack enough of the code to develop good intelligence. Additional intelligence came through the Japanese diplomatic cipher, which was cracked before the U.S. entered hostilities and broken consistently throughout the war. Japanese code makers, who invested a too great faith in their system, dealt with such possibilities by changing their codes periodically, and always before a major operation. This they did in December 1941, introducing JN-25b. (This new naval code effectively blinded the Americans just prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, with almost fatal results.)

Thus the war started, and apart from an ability to read some of their signals, the US Navy was not in particulalry good shape. Conduct of the War

Things did not get much better in 1942. The carrier LEXINGTON was sunk in the Battle of the Coral Sea and the carrier SARATOGA was damaged. The Japanese lost only one light carrier, and two fleet carriers were damaged.

When the carrier WASP had to be sent to the Atlantic, the line-up of naval power in the Pacific became 6 Japanese carriers to 3 American. Admiral Yamamoto, the architect of Pearl Harbor, was well aware that this superiority would be short lived, because the Yanks had shipyards. He had spent several years in the United States and did not underestimate its productive capacity.

Yamamoto knew he must strike quickly. If he could concentrate all 6 of his operational carriers against the American 3, the outcome could not be doubted. The attacking fleet would serve as bait to draw out the Americans, then finish off their fleet, and they chose Midway as for this. I don’t want to get side-tracked into a long discussion about the Battle of Midway, other than to recommend that you rent the movie (with Gregory Peck) which is very historically accurate.

At Pearl Harbor, the cryptographers worked around the clock at cracking JN-25b. Finally in April 1942, the pieces came together. Although only portions of each Japanese message could be read, they had enough to give Admiral Nimitz, the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, a shrewd idea of the Japanese plans and objective. This was where the famous “water message” was sent. The Commander US Forced on Midway Island was sent a message (by courier) instructing him to report, by radio, that he had a shortage of water. He duly did so. That message was intercepted by Japanese Signals Intelligence staff, who reported it to their Commanders, (using code JN-25b.) US Signals Intelligence then intercepted that coded message, advising of a water shortage at location “X” or whatever it was called; so they know that “X” was Midway.

On June 4, 1942, the Japanese lost all four of their carriers from the main striking force at the Battle of Midway. (Largely due to the efforts of Gregory Peck.) They were never able to recover from a loss on this scale.

The Merchant Shipping problem

The enormous Pacific expansion of the Japanese Empire in 1942 meant that Japan was dependent on the ability of its merchant fleet to resupply and reinforce its far-flung garrisons. At first, American submarines failed to neutralize this fleet. Their failure was due to inexperienced commanders; faulty equipment, particularly torpedoes; and the inability to find Japanese shipping. By 1943, however, everything was coming together. American submarine commanders were getting good at their job, torpedoes were improved and Navy code breakers began to read the Japanese merchant ship code.

Submarine commanders now got not only the number of ships in a given convoy, but often even their names, cargoes and escorts, and the convoy’s exact position. (Japan, which had started the war with some 6 million tons of merchant shipping, lost 5 million of it during the war.) So why is this relevant? The Submarine problem gave the Japanese something of a logistics headache. Their collection of booty, which consisted of the accumulated contents of the treasuries, banks, safe deposit boxes, jewelers shops and God knows what else from everywhere under Japanese control, was being collected in Manila, prior to shipment home to Japan. Then they realized that US subs were all over the Pacific and it was just too damn dangerous to send it back by sea, so that is how “Yamashita’s Gold” came to be buried it in the Philippines…...

Meanwhile, back at the ranch - in the Pacific - the Japanese have had their carrier fleet halved, but, at the same time, the US factories and shipyards have geared up and are knocking out aircraft carriers like Model T Fords….. US Naval Tactics in the Pacific

The limit of Japanese conquered territories extended as far as the northern half of Papua New Guinea, so that was where the effort of kicking them back to where they came from had to start.

American tactics in the pacific involved island hopping. Obviously, they had neither the men not the desire to winkle every last Japanese squaddie off every last coral bommie in the whole of the Pacific; they only needed to take some locations, they could by-pass the rest. They were left on isolated islands where they couldn’t really do much damage; the submarine offensive left them there without re-supply.

And so, very slowly, the war continued until, in May 1944, the Americans captured a bare assed lump of nothing just off the north coast of Papua New Guinea - this was the island of BIAK.

Biak was strategically significant, and caused the Japanese High Command to get their panties all in a bunch, because Biak is a relatively flat coral island - and by the time the Seabees bulldozers had gone over it and smoothed down the bumps, it was very flat; it was an airstrip from which they could launch aircraft that would be in range of the Philippines.

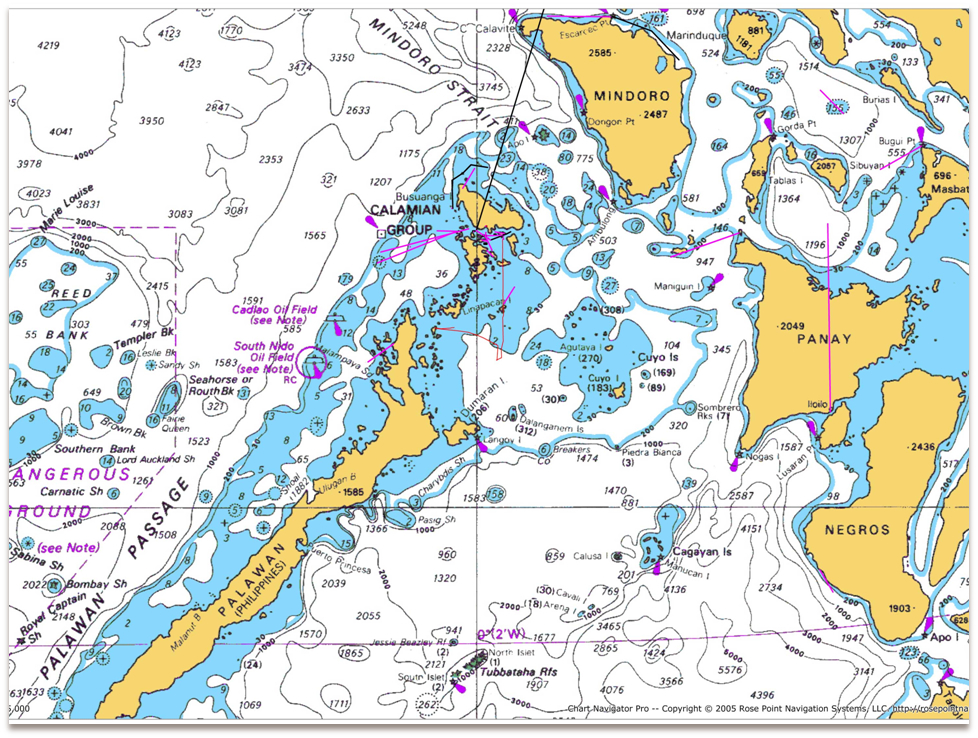

That was bad, so the Japanese fleet (such as it was) was ordered south, with instructions to kick the Septics off that damn island before they did any damage. They sailed south, and, I believe, en route, they sailed through the Busuanga Channel, giving the residents of Coron a view of the mighty Japanese fleet.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, even more bad news followed; the Americans had landed on SAIPAN. Now, to hell with Biak, Saipan was serious, because land-based bombers flying from Japan could reach targets in Japan - which was a whole lot more important than the bloody Philippines.

The fleet abandoned the idea of counter-attacking Biak, and turned North to deal with the more pressing problem of the American forces on Saipan. This had been expected, so the Japanese Navy did have a plan of how to deal with it; except for one thing; in their planning, the Japanese had expected the Americans to attack the Marianas - where they could sandwich them between the carrier fleet and land based aircraft based on Guam. Unfortunately, the Americans didn’t quite oblige them. There were also very serious communication problems between the Japanese Army & Navy, to such an extent that neither would actually admit the truth about their losses to the other for fear of losing face. This left the Navy to plan their battle with the support of land based (Army) aircraft which didn’t exist.

In any event, the battle of the Philippine Sea, better known as the Marianas Turkey Shoot. In the course of two days, the Japanese lost something of the order of 375 aircraft, together with what was left of their carrier fleet. That effectively ended any challenge to American air power in the Pacific.

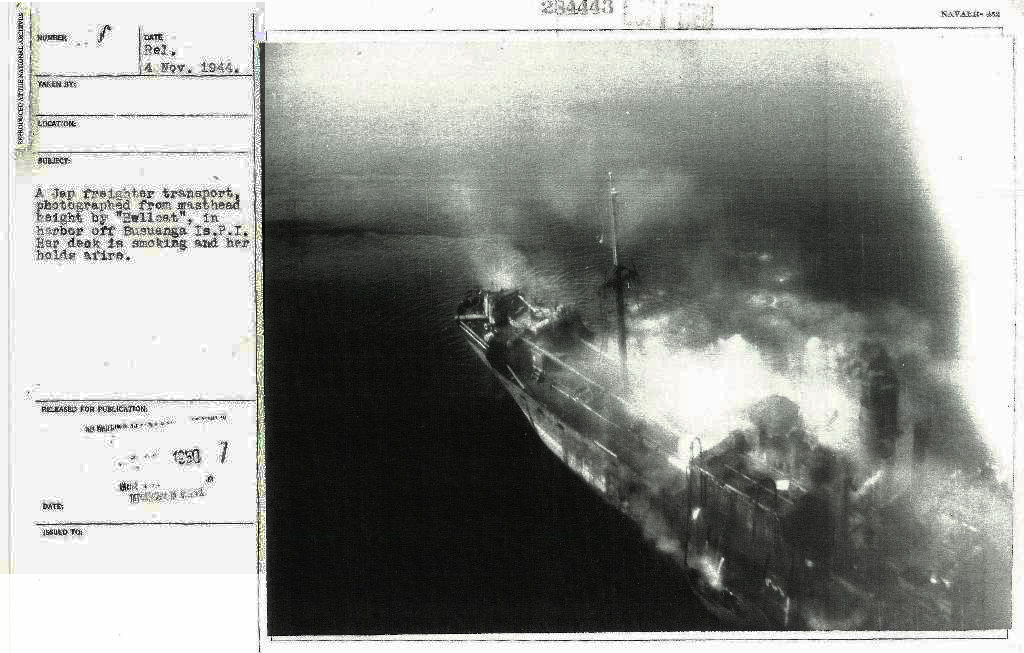

Why is this relevant? Because with effect from June 1944 onwards, the Japanese had very little air cover over the Philippines, so the US Fleet could more or less strike wherever they wanted. This they proceeded to do, whenever and wherever it suited them, and on 22 September 1944, aircraft from Task Group 38 hit Japanese shipping Manila Bay, (in full view of anyone standing around on Roxas Boulevard.)

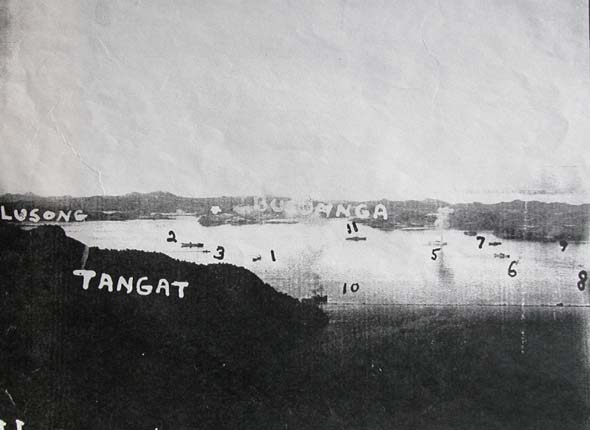

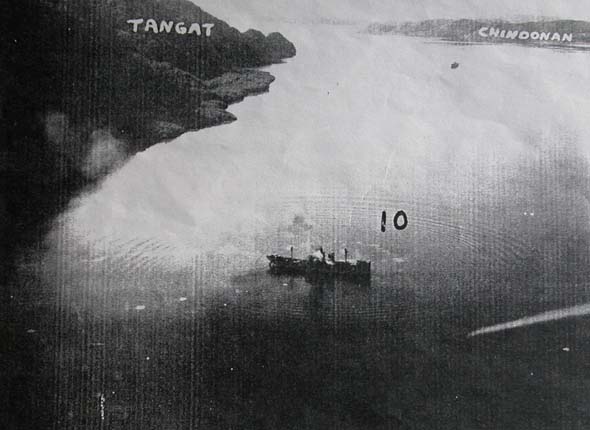

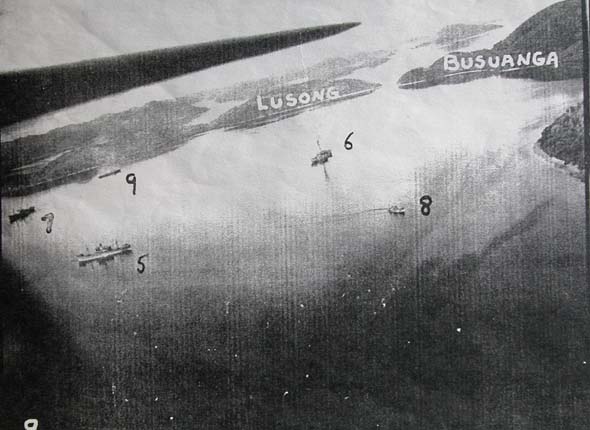

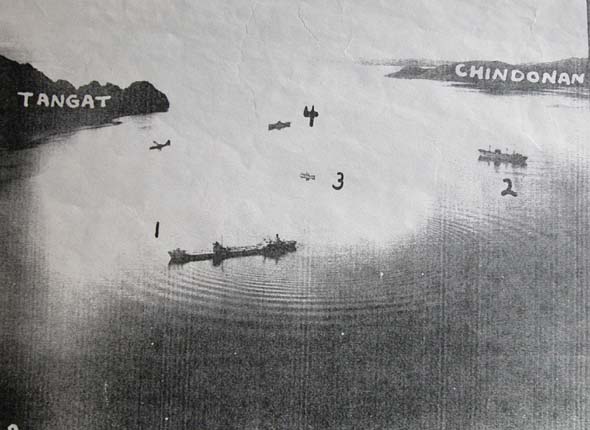

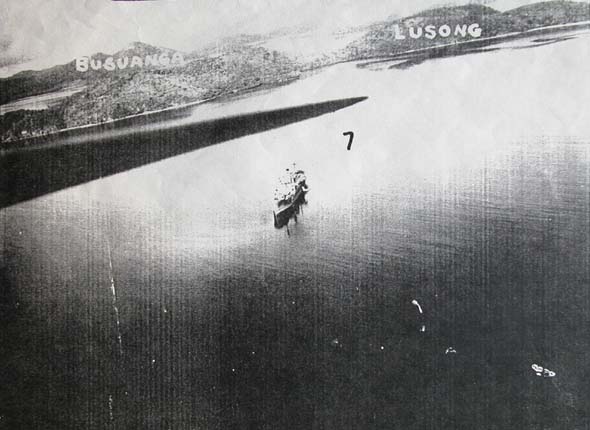

In order to try and protect what they had left, some of the Japanese ships were ordered out of Manila to anchorages in the Busuanga Channel, where they thought would be safe as they were out of range.

One of these was the IRAKO, a refrigeration ship which supplied the Musashi (or was it the Yamato?) They were bombed in Manila Bay on the 22nd then left for Busuanga, arriving there at 4 am on the morning of the 24th.

Meanwhile, Task Group 38 withdrew out to sea to the east of the Philippines to RV with their supply fleet, refuel and rearm, and then, during the night of 23/24th steamed back towards the Philippines again, to carry out orders received from Admiral Halsey during the course of day of the 23rd .

By about 5 am on the morning of the 24th, the carrier fleet was in position, about 50 miles north-east off the cost of Samar, they turned into the wind and the first wave of aircraft were launched about 0530.

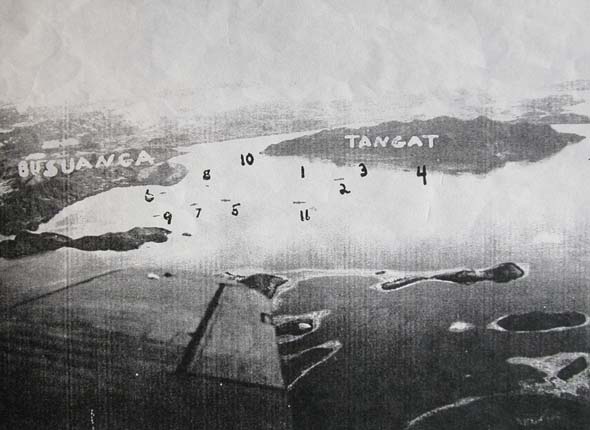

Now, where did Halseys orders come from? There is an anecdote about how the ships were identified at Coron; the story is that there was a photo reconnaissance flight that passed overhead and took pictures of what were thought to be islands. Then, the story goes, a second flight photographed the area again, whereupon some sharp eyed Air Photo Interpreter realised that these “islands” had turned on the tide.

Nice story, but untrue.

The Coron Raid

The Result

The Research Effort

Of the 12 carriers whose aircraft participated in the raid, the records of only six remain in the archives. As it turned out, one of those was the USS Intrepid. More significantly, it became apparent to me that the story of the air recon was patently wrong.

Our primary goal on this research project had been to determine whether or not there were any more shipwrecks in the area. The way we could do that, was to match up the Action Reports from the carriers with other information, such as the JANAC list, but with an incomplete set of Action Reports, it was not really possible to do that.

The report from the USS Intrepid, however, opened up a new and interesting search all of its own. Of the 12 SB2c Helldiver aircraft from the Intrepid, 3 failed to return to the ship, and despite what it said in the Post Action Reports, we now know that all three were shot down over the target area.

In the narrative section of his report, the Intrepid officer concentrated on the loss of these aircraft, particularly on Lt BEATLE's plane; describing the position where he made a water landing. This was the first indication that we might find an aircraft in the water, and thus began the search for both the aircraft and the crew.

Initially, using the various computer search facilities available to me on the Internet, I failed. However, Helen Farrell had been able to supply me the contact details of the USS Intrepid Association, and it was Larry Blackburn who was able to give me next and most important piece of information; Lt BEATLE's crewman, Ralph JOHNSON, was still alive and was a member of the association.

For me, Mr Johnson's address was a reward that justified all the time and effort I had spent in carrying out the investigation. For Mr Johnson, however, it was something of a surprise; more than fifty years after it happened, somebody wrote him a letter from the other side of the world, asking him if he could remember where, exactly, his plane ditched because some people were looking for it!

On my next trip back to Coron, we began to dive the area searching for the elusive wreck of Ralph Johnson's plane. We began by diving at the precise location detailed in the report. Visibility there was almost nil. We dropped through the thick blue water until, at 130 feet, we made our own unceremonious belly landing on the sand bottom. We could hardly see each other, far less any wreck! A few similar efforts resulted in similar nil returns, so we gave up for the day and went to try something else instead. We found an old fisherman who sent us to see his son Dodong. Yes, Dodong knew where there was a plane; which he described as being about 24 arm spans deep near the corner of the reef It was a single-engine plane, sitting upright, but with one wing folded over the fuselage, and he estimated it would weigh about one ton. The description could well fit a carrier based bomber like the Helldiver. We were confident we were on to it.

The only problem was that Dodong had not actually seen the plane himself, but his friend had. His friend had been diving, using hookah apparatus, collecting seashells, and had chanced upon it quite by accident. All we had to do now was find that same location, and dive on it again. Easier said than done, but, the fact remains; it is still there - and as they say: it’s not “lost,” its only wet! |

Deep Down YOU want the Best, |

Money can buy for You and Your Loved Ones. |

| WWII | ||

|

||

.jpg)

.jpg)